As civil society organizations, governments, and corporations convene later this month for the Generation Equality Forum, gaps in the gender data needed to monitor the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) belie the commitment to advance gender equality.

In fact, in the 25 countries studied in Data2X and Open Data Watch’s assessments of gender data in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Asia and the Pacific, only 50 percent of all indicators have sex-disaggregated data, 18 percent lack sex disaggregation, and 32 percent have no data at all—with gender data gaps found in every country.

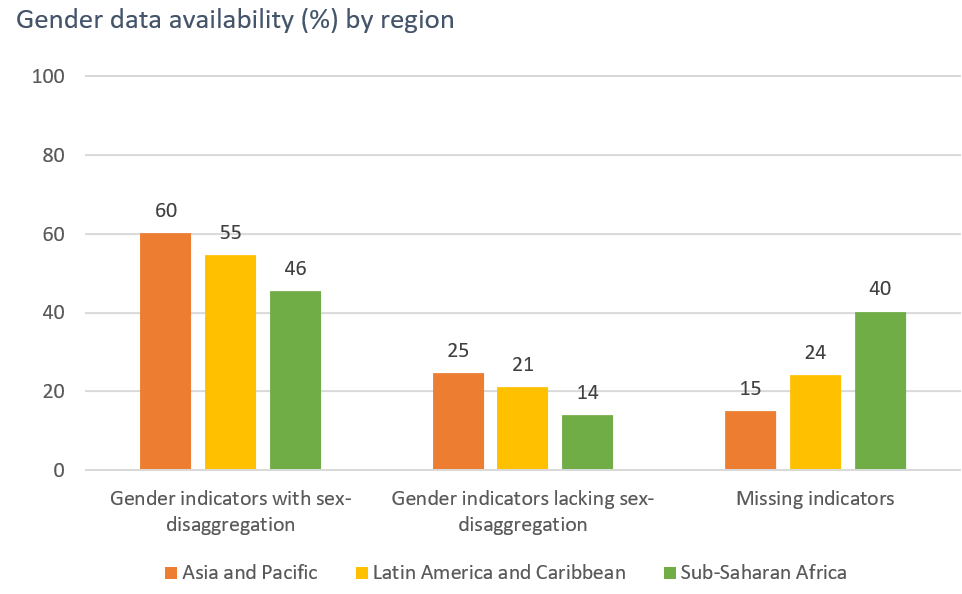

Regionally, Sub-Saharan Africa has, on average, the fewest sex-disaggregated indicators and the largest proportion of missing indictors, while Asia and the Pacific has the largest proportion of available, sex-disaggregated indicators. This dearth of gender data prevents us from understanding key aspects of women’s and girls’ lives and creating, monitoring, and refining policies that reflect their interests.

Facing these substantial gaps, what is a “quick” win? The first step is to publish sex-disaggregated data for the indicators lacking disaggregation. In our new panoramic assessment on the state of gender data across all regions, we found that if all indicators for which there are currently any data were published with sex-disaggregation, gender data availability would rise to 85 percent in Asia and the Pacific; to 76 percent in Latin America and the Caribbean; and 60 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa.

This statistic demonstrates a massive opportunity to close gender data gaps; in many cases, countries already have access to these data through existing surveys and administrative sources. For example, household health surveys and labor force surveys collect basic information, such as the age and sex of household members, while administrative sources can produce sex-disaggregated data on education participation, disease incidence, and criminal justice.

Whether these data are used and published ultimately depends on the country’s administrative system capacity to collect accurate information on age and gender. But by publishing existing high-quality, disaggregated data, we could potentially see significant increases in the gender data available for policy, planning, and analysis.

Yet more and better disaggregated data only solves part of the problem. Missing indicators continue to exacerbate data gaps. Fifteen percent of the SDG gender indicators have no data within the last 10 years in Asia and the Pacific; 24 percent are missing in Latin America and the Caribbean and; 40 percent are missing in Sub-Saharan Africa. If countries cannot produce indicators that conform to standards and definitions listed in the SDG metadata repository, they should consider alternative, non-conforming measures.

From our analysis, we already see countries doing just that. In Malawi’s national databases, for example, 21 out of the 68 indicators are non-conforming, 18 of which are sex-disaggregated. While producing non-conforming indicators can reduce international comparability, such indicators are often closely aligned with national or local policies and practices.

Aside from monitoring data points, we are also mindful of the importance of data timeliness and frequency. Timely data are critical to implementing and monitoring the SDGs. In a world of rapidly changing events requiring up-to-date evidence for informed decision-making, old data are quickly forgotten. Delays in data publication reduce the value and usefulness of the data. And frequent observations of data are needed to implement policies and strategies and to monitor progress to national development plans and the SDGs.

Across the 25 countries, the median lag between the most recent year of observation and the year of publication was three years. But some countries do much better. As shown in their Bridging the Gap country profiles, for example, South Africa and Costa Rica conduct annual multi-topic household surveys and labor force surveys, while Armenia conducts annual living conditions surveys and labor force surveys. Other countries collect data less frequently or experience prolonged delays in updating indicators.

The major goal of the Generation Equality Forum is to coalesce civil society groups, governments, and corporations to “define and announce ambitious investments and policies.” Gender data are fundamental to monitoring any gender policies set forth by the Forum.

With better planning, improved processes, and, in some cases financial support, countries can increase the availability and quality of their gender data by:

- Using existing survey and administrative data sources to replace aggregate data with sex-disaggregated data;

- Increasing the frequency of data collection and reducing delays in publication;

- Publishing non-conforming indicators with sex-disaggregation, as needed; and

- Aligning their national strategies for the development of statistics with the requirements of their gender strategies.

These actions will be critical in realizing the goal of gender equality.