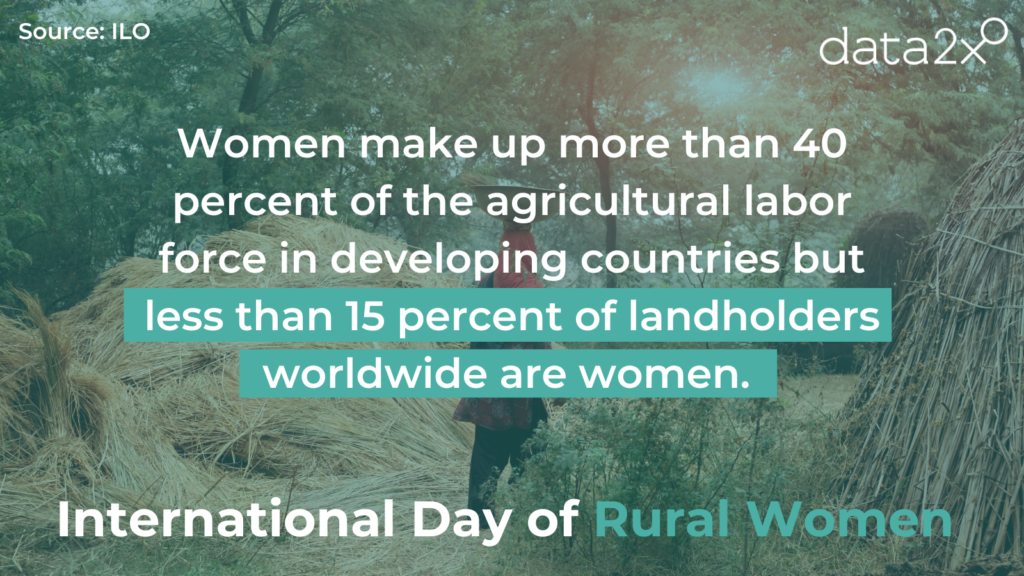

On average, women make up more than 40 percent of the agricultural labor force in low and lower middle-income countries but less than 15 percent of landholders worldwide are women. International Day of Rural Women highlights the “critical role and contribution of rural women, including indigenous women, in enhancing agricultural and rural development, improving food security, and eradicating rural poverty.” Ahead of the International Day of Rural Women, Data2X connected with Salonie Muralidhara Hiriyur, a consultant with Data2X’s partner organization Self-Employed Women’s Association Co-operative Federation (SEWA), to understand the unique constraints that rural Indian women face and how co-operatives are uniquely designed to serve and empower rural women.

Note responses have been edited for clarity.

Question (Q): What are the unique challenges that rural women face in India?

Answer (A): India is primarily an agrarian country where most people rely on agriculture for food and incomes. We have been seeing an increasing feminization of agriculture, with the migration of men into cities and farming being left to women.

The first challenge I see is identifying women as productive workers, as contributing workers—as farmers even—isn’t prevalent. One of the reasons for this is that usually attributing the title of ‘farmer’ to a person is tied to land ownership. But women don’t own the land, they don’t own any of the things that they rely on for their income and food and so they are not recognized.

Second, the availability of financing, markets, along with social norms (women do not have bank accounts, are not as mobile, and don’t have access to public transportation), leads to them not being able to engage with all aspects of the agricultural supply chain. They’re doing the demanding work in the field, but they’re not going to the market and so they’re not receiving income directly for their labor.

Thirdly, we see climate change impacting farming. The activities of the global north are contributing to rising temperatures, the effects of which are felt most greatly in the global south, in countries like India. Farmers are losing the ability to grow crops the way they used to and so must change the way they farm. But knowledge about different farming methods may not be accessible to them, particularly women. There’s a large amount of capacity building and financing that goes into combatting challenges that arise due to climate change that are not reaching women, or any farmers, most of the time.

Q: What is the SEWA Co-operative Federation and how does your work impact rural women in India?

A: SEWA is about 50 years old, and we are a trade union of 2.1 million women workers of the informal economy in India. This includes farmers, who form the large part of our membership, but also handicraft workers, small scale manufacturers, home-based workers, street vendors, domestic workers, basically any woman who works without the traditional employer-employee relationship. Alongside being a union, SEWA also organizes women into a social solidarity economy. The logic is that women workers should have complete ownership both financially and in terms of decision making around their work without being exploited by middle agents. And they should have protections that the state is not able to give them such as healthcare, childcare, and insurance. SEWA’s entire support ecosystem makes these very basic resources available to the women through their own co-operatives.

Q: How are co-operatives unique in serving rural women?

A: Co-operatives are revolutionary; they are democratic and owned by workers. Women who otherwise would not have any capacity or power to make decisions are now governing and running their own co-operatives and making decisions on farming, how money should be spent, and what they should market. So, it gives them immense power and a voice which they otherwise did not have.

Ela Bhatt, our founder, uses this example: one woman in a very remote village in India milking a cow has no voice, but when she joins a milk cooperative, suddenly she’s with 100, 200, 300 women who are also milking cows. She is able to relate to them and to build that solidarity network, and all of them now have a voice, particularly for rural women, given their location and the lack of resources reaching them, this is crucial.

Q: What actions should policymakers take to support rural women?

A: The first thing is to recognize women as workers and promote their co-operatives. When SEWA started, the idea that women’s co-operatives could be businesses was absurd to the State and the registrar. We have a childcare co-operative now but when we went to register it 30 years ago the office said, “But childcare is women’s work anyway. What do you mean by building a co-operative around it?” It took us years to actually register the co-operative. A lot has changed, but there’s still work that needs to be done. Recognizing that women-owned businesses, collective businesses, and co-operatives are viable options is important.

The second thing that SEWA believes very strongly is that without universal social protection, we won’t get very far. You can give a woman a steady income, but unless she has access to healthcare, she’s likely to spend it all when she has an accident. Our women say, “my body is my only asset and so I need healthcare to protect my only asset.” Childcare is crucial because without it, women are not able to engage with the paid labor market. Insurance is crucial, whether it’s for herself or her family, for crops, or for land. And these social protections must be offered by the state, and they must be universal, because otherwise the people who get excluded are the rural women.

Policymakers should also support organizations, like SEWA, which provide a holistic ecosystem and base-up approach through which they will get results. Policymakers these ecosystems because they are creating an environment of financing, market linkages, capacity building and training, which is so crucial for the co-operatives and their members to survive, sustain and grow.